Novel Coronavirus - Summarizing Japan's Strategy, Response and Result

Contents

- Why is Japan considered successful?

- What was Japan’s strategy?

- Declaring a State of Emergency

- How did the Japanese population react in practice?

As of June 13th 2020, Japan appears to have successfully controlled the spread of the novel coronavirus. Noone is sure exactly why.

This blog post is a rough and abbreviated summary of the factors at play, occasionally digging a little deeper into the evidence and providing additional reading material.

Why is Japan considered successful?

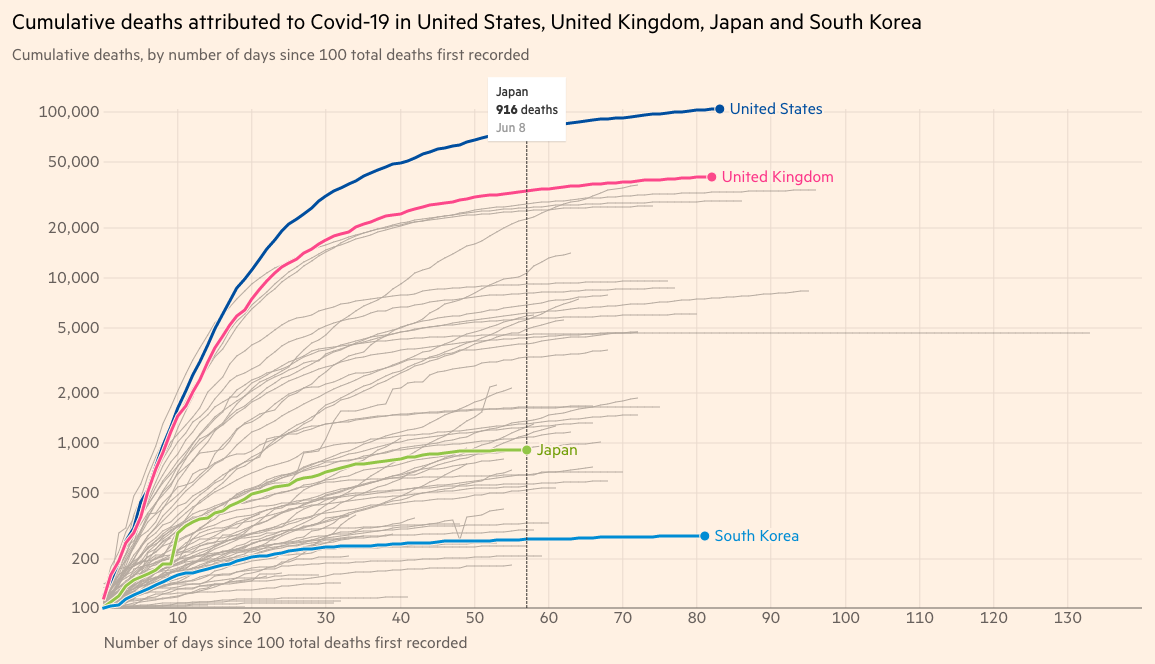

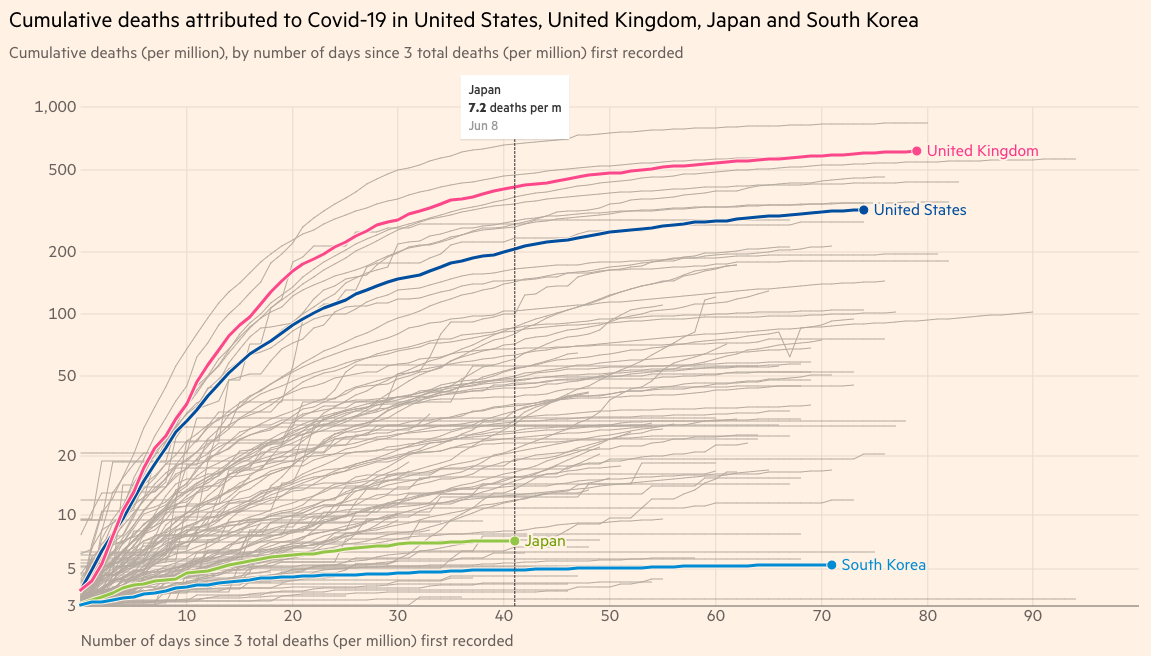

According to data provided by the Financial Times (as of June 8th 2020), a total of 916 people have died with the cause attributed to COVID-19.

This equates to 7.2 deaths per million.

While Japan’s result compares very favourably with that of some western countries, it is quite typical of Asian countries. Japan has performed far worse than countries such as Taiwan (now 7 recorded deaths) and Vietnam (still 0 recorded deaths).

Any concerns about the accuracy of the data?

Every now and then I see a comment that a number of COVID-19 deaths are misclassified as pneumonia so the death figure is actually much higher.

To factor in misclassifications you would consider total excess deaths by any cause relative to a baseline constructed from previous years. This report from Bloomberg suggests around 1,000 excess deaths over April compared to the baseline. Corey Wallace, assistant professor at Kanagawa University, suggests that the 104 COVID-19 deaths officially recorded could well be accurate and it is very unlikely for the real total to be above 500.

What was Japan’s strategy?

Japan implemented a strategy that roughly translates to “Counter-cluster Measures”.

I tweeted my translation of the official strategy doc here.

The Japanese government created a task force that tried to grasp the origin of clusters and prevent spread by:

- Detecting outbreaks of patient clusters

- Identifying group outbreaks at an early stage through notifications from hospitals/clinics.

- Searching for the infection origin/route

- Conducting a focused investigation starting with the infected person to understand how the infection may have spread.

- Implementing measures to prevent spread

- Health monitoring of those who came into close contact with the patient and requesting that they self-isolate voluntarily. Companies and other establishments related to the patient will also be requested to close and cancel activities such as events.

Why focus on clusters?

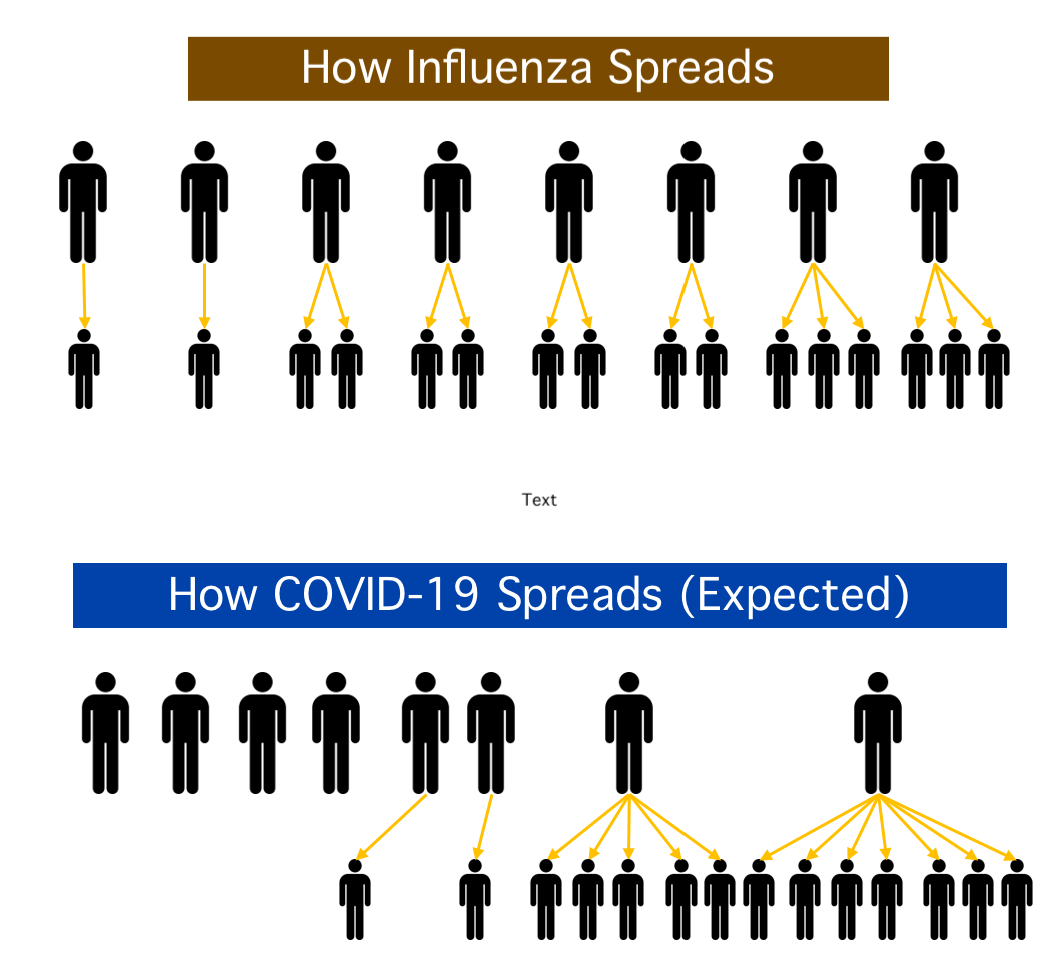

Analysis of the first few cases in Japan indicated that while most people infected would not pass on the infection to others, a few would go on to infect many others in a so-called “superspreader” event.

Is there any further evidence that COVID-19 spreads in this way?

In addition to the now well-known R (reproduction number) measure, scientists also use a value called the dispersion factor k. A lower k value indicates a smaller number of people contributing to total transmission. There is some evidence that k is low for COVID-19 summarized here.

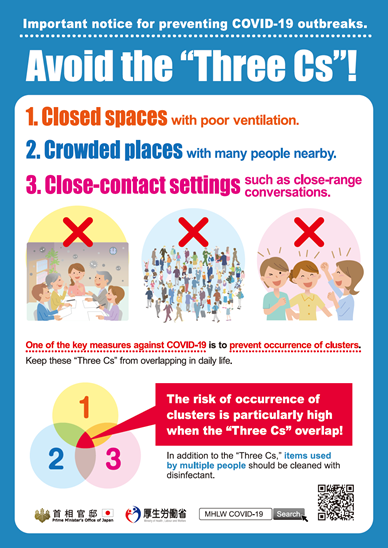

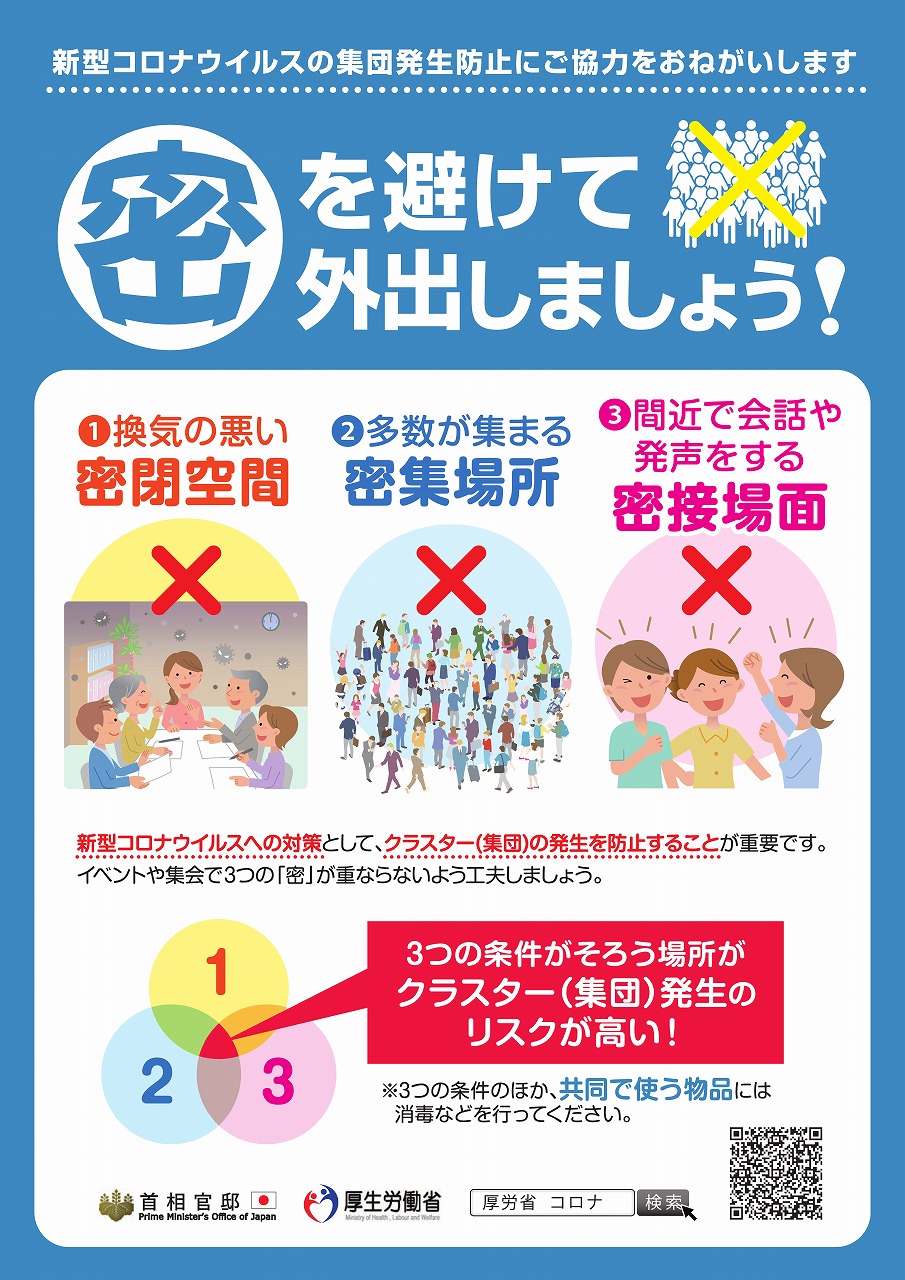

Experts in Japan theorized further that “superspreader” events were much more likely to occur in places that met the 3 conditions below:

- Closed spaces with poor ventilation

- Crowded places with many people nearby

- Close-contact settings that facilitate close range conversations.

High-risk locations were identified after finding that the first clusters in Japan were formed in places such as fitness gyms, restaurants and hospitals.

Is there any further evidence that certain locations facilitate spread more than others?

It is common sense to expect places that meet the 3Cs to be particularly high risk. It is less intuitive for a location to meet conditions 1 & 2, but the absence of face-to-face contact and active conversation in condition 3 to have such a suppressing effect on transmission. Here is a good explanation of why this actually may be quite intuitive, under the heading: “Risks Follow Power Laws”.

The fact that all 3 conditions must be met was picked up in Japan early, noting that packed trains do not typically facilitate clusters since people are generally wearing masks and not talking to each other. As a resident of Japan for 8 years, I can verify that talking on your phone or even friends in a loudish voice on a train is somewhat taboo. Outside Japan, there was also evidence from France that no clusters formed in public transport.

Further evidence that breathing/talking can facilitate spread here.

Travel bans

Like many countries, Japan implemented a widespread travel ban to deny entry for anyone that has stayed in a long list of countries up to 14 days before landing.

In addition, anyone who is able to land must take a PCR test upon entry and be quarantined in a location specified by the quarantine station chief for 14 days. They are also requested to refrain from using public transport.

Are travel bans effective at controlling spread?

Dr. Cassidy Nelson, who studies catastrophic biological risks at the Future of Humanity Institute, suggests the following on travel bans (summarised nicely here):

-

Models analysing the effectiveness on travel bans during prior outbreaks (particularly 2009 swine flu) suggest that while bans cause a delay in the peak of cases, the magnitude of cases does not change.

-

They often create perverse incentives for people and countries. People might travel through certain locations to get from A to B, or you might accidentally prevent shipments of important items such as PPE equipment from getting to where it is needed.

-

If a country already has a number of cases (such as Japan at 17,000+ cases as of June 8th 2020), there is already a high degree of person-to-person transmission. Opening up travel would only account for a small % of cases even if no preventative measures are taken.

Closing Japan off temporarily was a good move when dealing with such high degrees of uncertainty at the beginning of the pandemic. Going forward, I’m not convinced it would achieve much of a positive outcome.

A lack of testing?

Many outside observers initially raised concerns that Japan wasn’t testing enough and a number of actual cases may not be accurately portrayed in official numbers.

Government officials argued that the PCR tests available at the time were unreliable and false positives in testing would only serve to stretch already limited resources and over-burden medical institutions. False positives are particularly troublesome when your strategy is to spend copious resources actively identifying and managing clusters.

A relative lack of deaths in Japan suggests that concerns in March that many cases may have been hidden were either misplaced or a higher than expected % of cases are asymptomatic.

Are PCR tests unreliable?

No test is 100% perfect. Current literature suggests that PCR tests have low-moderate sensitivity (around 70%) but high specificity (around 95%). A test with low sensitivity will fail to detect actual cases, while low specificity will produce positives where there is no infection.

Back in March I tweeted a summary translation of a report of cases from the Diamond Princess, which included some information on low PCR test sensitivity. More evidence for low sensitivity can be found here and here.

As for specificity, 95% is considered high. However, a comprehensive testing program of 100,000 tests per day would still detect 5,000 cases where there are none. Setting to one side the burden of dealing with these cases in various medical institutions, you would also add so much noise to the signal required to conduct the aforementioned “counter-cluster” strategy that it may be rendered ineffective.

Data availability and accuracy

Testing in Japan was conducted by a mix of public hospitals/medical facilities and private facilities. Data provided by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) only took into account figures reported by public facilities.

In Tokyo, that changed in early May when data for all institutions was released dating back to January. I’m unsure how the integration of this data affected overall figures.

Other than data provided by the MHLW, a dashboard containing case data from regular media reports can be found here (see dashboard details for data source info).

As with much COVID-19 data globally, Japan’s data is fragmented and difficult to interpret.

Declaring a State of Emergency

(This content taken from a tweet by Derek Wessman.)

While some countries were able to order curfews and ban events in a legally enforceable way, Japan’s constitution does not allow this:

“Freedom of assembly and association as well as speech, press and all other forms of expression are guaranteed.”

However, Japan does have a “Novel Influenza Etc Special Measures Law” that enhances government power during a pandemic. Through this law, the government can request (Japanese: 要請, yōsei) the public and businesses to take certain measures.

The Japanese word here is a strong word coming from the government, and under the Special Measures Law, failure to comply with some requests can result in government action.

What is a State of Emergency?

I found it difficult to find exact information in Japanese or English on the precise definition of the state of emergency. As far as I can tell, it enables local governments to make requests as per the “Novel Influenza Etc Special Measures Law”.

The following information is a rough summary of a PDF entitled “What is a state of emergency?” (Japanese only) from the Hokkaido prefecture website. The messaging used here may be useful information for other cities and countries attempting to find a balance between curtailing spread and reopening their economy.

(Note that these guidelines are specifically for Hokkaido, other prefectures may have slight differences.)

Page 1: The state of emergency is a set of guidelines for all people, businesses and local governments to follow to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Page 3: Be extra diligent in taking preventative measures such as washing your hands and wearing masks.

Page 4: Stay home as much as possible, except for activities essential to your lifestyle. Essential activities include:

- Health-related activities such as going to a clinic/hospital, outdoors exercise.

- Buying essential items.

- Going to your workplace etc.

Page 5: For those continuing to work, the following are encouraged:

- Staggering working hours to avoid congestion on public transport.

- Avoiding locations that meet the 3Cs.

- Working from home.

Page 6: Avoid establishments in business districts used for settai (corporate entertainment)

- Avoid bars, nightclubs and restaurants.

- Avoid karaoke and live venues.

Page 7: Avoid unnecessary traveling, particularly across prefecture borders. This includes traveling during Golden Week.

Page 8: Closing high-risk facilities. Establishments serving alcohol are requested to stop serving from 7pm.

Page 9: Refrain from hosting events or parties in places that meet the 3Cs.

Page 10: Keep a safe distance from people. A rough guide is to maintain a distance such that your hands wouldn’t touch if both people stretched them out to their side.

When does a state of emergency end?

The criteria to end a state of emergency is not set in stone, but there are some guidelines to help make a decision. The following items are taken into consideration:

1) Infection situation

- A declining number of cases.

- Due diligence with respect to new clusters, the number of infections in medical institutions and infections with unknown origins.

- The infection situation of neighbouring areas (i.e. adjacent prefectures)

2) Medical service system

- A consistent decrease in patients with severe symptoms.

- Hospital bed capacity.

- Whether or not a system to respond to a sudden increase in patients has been prepared.

3) Surveillance system

- Whether or not a system to administer PCR tests without delay has been prepared.

The complete official guidelines in English for lifting the state of emergency can be found here.

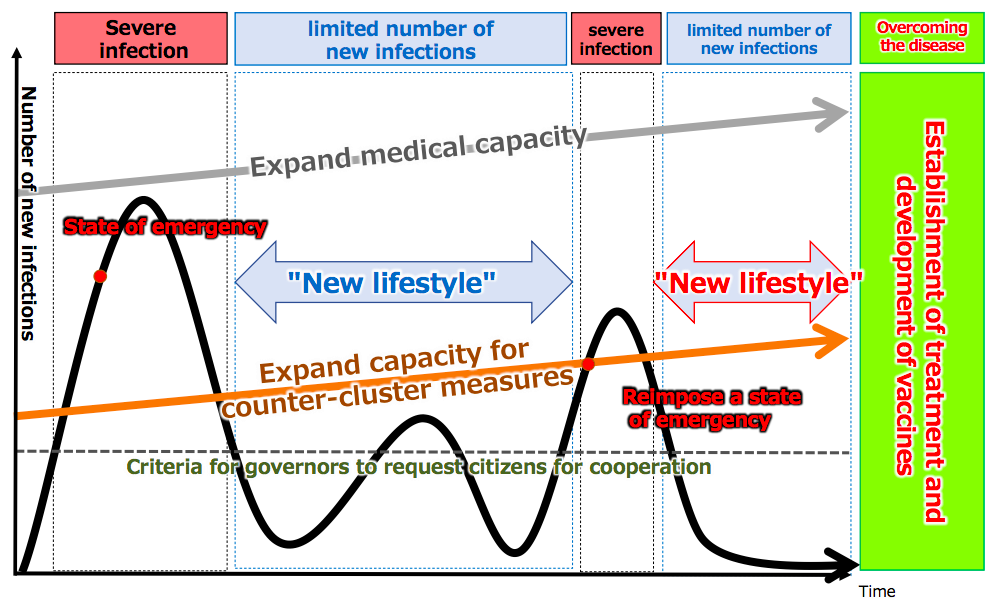

The Japanese government is expecting to cycle through periods of a state of emergency as required in an effort to flatten the curve and expand medical capacity/counter-cluster strategy resources.

What stops individuals/businesses from acting as normal in the absence of a legal threat?

As noted by many other commentators, there are strong norms around not being a bother to others in Japanese culture.

In addition, if the government makes official recommendations to engage or disengage in certain behaviours, the population tends to take such recommendations seriously.

While some businesses were also requested to close, it is interesting to note that they have no legal requirement to do so. If a request is ignored, the subsequent recourse is to issue a stronger instruction (Japanese: 指示, shiji) or even publicly announce the offending establishment in an effort to tarnish its reputation (note this story naming 20 pachinko parlours in Kanagawa prefecture). This article speculates on whether or not there is a legal precedent to levying fines or stronger legal measures against nonconforming businesses.

How did the Japanese population react in practice?

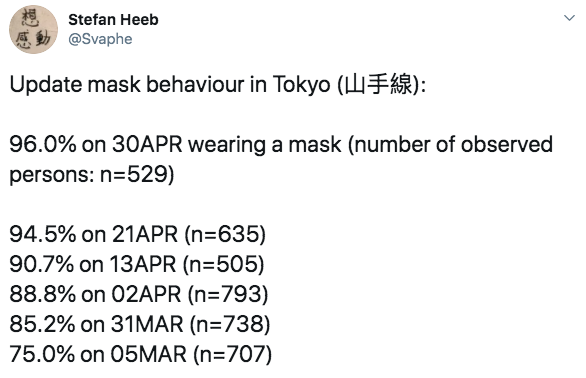

Mask Wearing

While masks were quite scarce in February/early March, they are now widely available. Social scientist Stefan Heeb has been tracking mask usage on Tokyo’s Yamanote Line. He found that mask wearing has been steadily increasing, now up to 96% (n=529).

Does wearing a mask help?

Despite conflicting advice from WHO at the start of the outbreak, evidence has pointed somewhat towards masks having a large effect on preventing infection. A meta-analysis of ten studies with results related to mask wearing published in Lancet (June 1st, 2020) states:

“Medical or surgical face masks might result in a large reduction in virus infection; N95 respirators might be associated with a larger reduction in risk compared with surgical or similar masks.”

It is worth pointing out that this finding was stated with a low degree of certainty, the effect of mask wearing could be quite different.

Using Hand Sanitizer

Living in Tokyo, I’ve found hand sanitizer to be widely available and people seem quite diligent in using it regularly (it was freely available at the entrance to the office of the Japanese company I worked at).

The only free data I could find on hand sanitizer usage by country was on Statista, where they offer a figure for average revenue for the hand sanitizer market per capita. 2019 spend on hand sanitizer was estimated at $0.73 and $0.72 per capita for the US and Japan respectively. This suggests little difference in hand hygiene between the two (although I’m not sure this is the case).

(Any data I could get on Japan’s use of hand sanitizer relative to other places would be welcomed!)

Extra Measures Taken at Shops/Restaurants etc.

A number of measures have been taken to prevent spread in brick-and-mortar locations:

- A vinyl sheet between the customer and cashier.

- Hand sanitizer available at the entrance/in bathrooms + signs to encourage use.

- Staff wearing masks at all times, signs to encourage customers to do the same.

Below is an image of mexican restaurant Guzman y Gomez in Shibuya, which was partly open inside but conducted most of its business as a take away outlet with this makeshift counter:

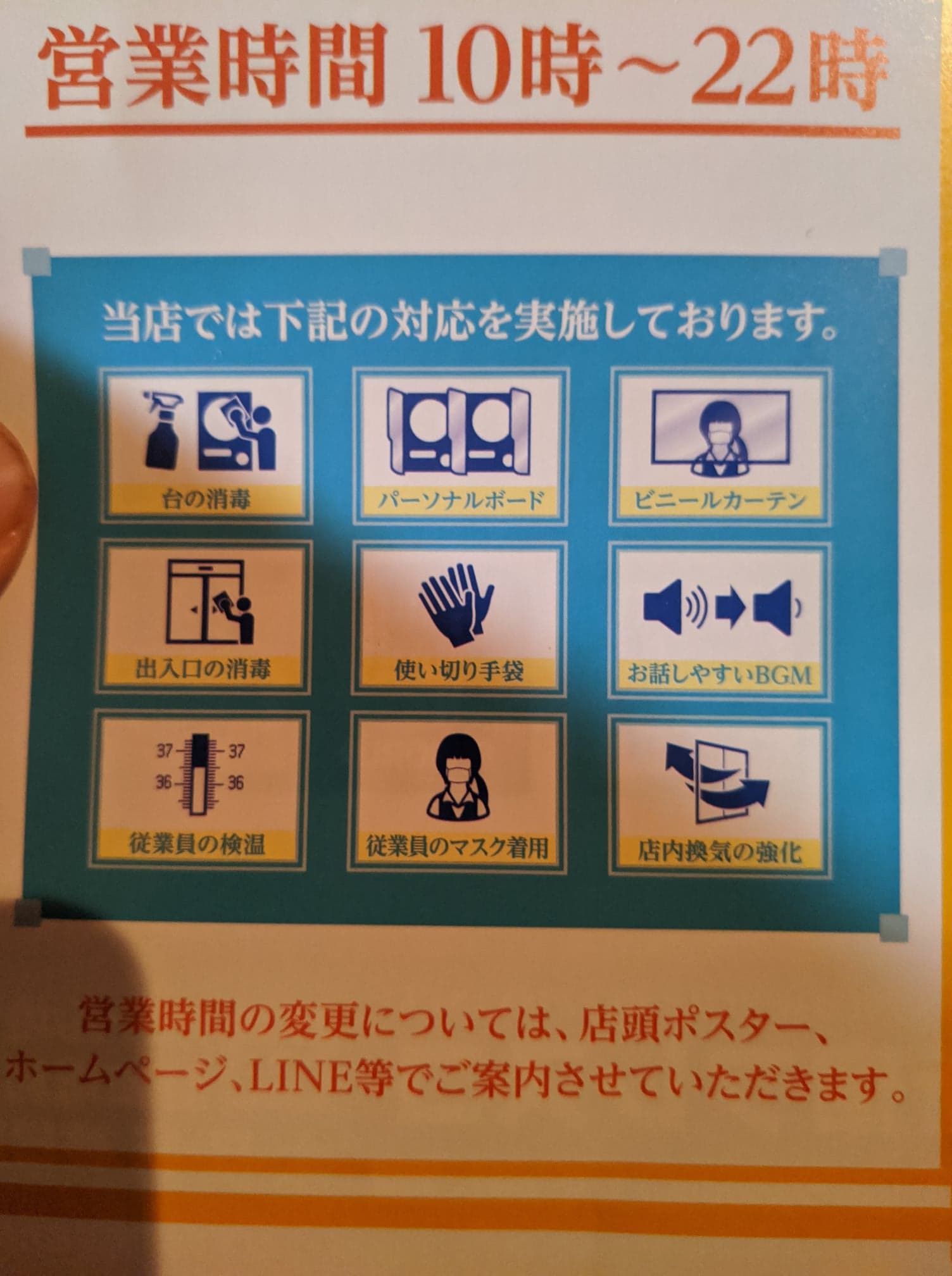

This pamphlet was also delivered to my letterbox outlining the various preventative measures taken by a local pachinko parlour:

Measures here include:

- Disinfecting the pachinko machines

- Separating panels

- Vinyl curtain between customer and cashier

- Disinfecting the entrance door

- Disposable gloves

- Music turned down for easier conversation

- Temperature checks

- Masks for staff members

- Stronger ventilation

In conjunction with the “counter-cluster” strategy, certain establishments like bars and karaoke parlours also follow a protocol to check the body temperature and take down contact information of all entering customers so the route of infection is easier to trace in case of an infection.

Going to the Office

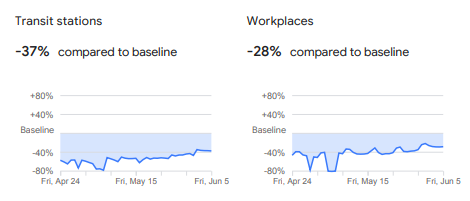

Tokyo has seen a reduction as much as 80% in commuting to the office during the periods of the state of emergency, but now sits around -28% relative to baseline (as of June 6th, 2020):

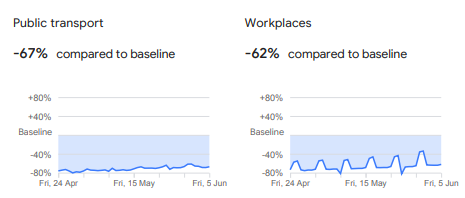

The same data for Greater London shows a more sustained drop, currently around -60% (as of June 6th, 2020):

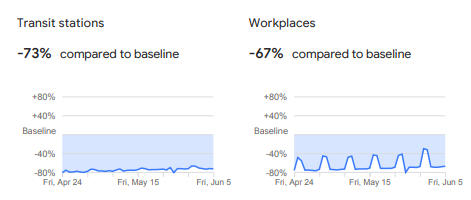

New York County shows a drop to -67% relative to baseline:

This suggests that public transport and offices are still being used frequently without too much of an effect on spread.

Continued use of places that didn’t meet the 3Cs.

Messaging from the Japanese government on what places to avoid has been pretty clear, but my impression is that places that fit 1 or 2 of the 3Cs have only seen a slight reduction in use. This would include places such as:

- Stadia

- Parks (for cherry blossom viewing, day out with the family etc.)

- Public transport

If such places are being used continuously without causing a significant uptake in infections, a similar kind of messaging could be effective in other parts of the world.