Moral Uncertainty Tool

Having really enjoyed listening to 80,000 Hours episodes featuring Will MacAskill, Hilary Greaves, Toby Ord and the recent interview with Christian Tarsney, I decided it would be fun to dig deeper into a specific area to gain a more in-depth understanding.

This post focuses on the book Moral Uncertainty, authored by Will MacAskill, Krister Bykvist and Toby Ord, which lays out a theoretical approach to taking an expectation across moral theories in a way that is analogous to empirical uncertainty.

Since the authors of the book lay out an explicit approach, I have also attempted to create a Moral Uncertainty Tool in Google Colab (Python) that allows the user to:

- Add ordinal and interval-scale (cardinal) moral theories.

- Add their credence in each theory.

- Add the choiceworthiness of different options by the lights of each theory.

- Output the most choiceworthy option given the above.

*In its current state, this tool is quite user-unfriendly. To use, copy a version of the tool to your Google Drive. Further instructions at the bottom of this post.

For the reader, please bear in mind that I am by no means an expert at any of the topics touched upon here, and my summary and tool may contain mistakes.

Much of this post is simply a rearranging of the ideas in Moral Uncertainty and my interpretation of those ideas. I claim no part of these ideas as my own work; full credit goes to the authors. Any and all mistakes my own.

Moral Uncertainty has some focus on the following, not covered in this post, including:

- Justification of taking an expectation of moral uncertainty in the first place.

- Objections to arguments that suggest that intertheoretic comparisons are impossible.

- Discussion on metaethical and practical implications.

I wholeheartedly recommend anyone interested in a much more coherent and comprehensive version of this post to read the original book!

Maximizing Expected Choiceworthiness (MEC)

The choiceworthiness of an option refers to the strength of reasons for choosing that option, by the lights of a given moral theory.

Definition: When we can determine the expected choiceworthiness of different options, A is an appropriate option iff A has the maximal expected choiceworthiness.

MEC is based on the premise that moral uncertainty can be treated analogously to empirical uncertainty.

As explained in Moral Uncertainty:

“While expected utility theory is the standard account of how to handle empirical uncertainty probabilities, maximized expected choiceworthiness should be the standard account of how to handle moral uncertainty.”

Intertheoretic Comparability

When dealing with empirical uncertainty, an expected value calculation takes into account the probability of an outcome * magnitude of that outcome.

However, attempting to take an expectation of choiceworthiness across moral theories hits a stumbling block when you consider how structure of individual theories may differ.

Amplified theories

Two or more theories that have both interval-scale measurability and unit-scale comparability.

Example: Two different forms of utilitarianism, one of which is an amplified version of the other.

From Moral Uncertainty (page 129):

“Consider Thomas, who initially believes that human welfare is ten times as valuable as animal welfare, because humans have rationality and sentience, whereas animals merely have sentience.

He revises this view, and comes to believe that human welfare is as valuable as animal welfare. He might now think that human welfare is less valuable than he previously thought because he has rejected the idea that rationality confers additional value on welfare.”

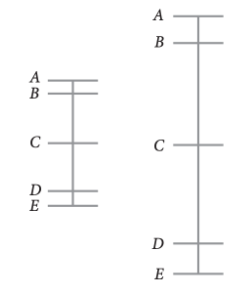

See the image below for a visual representation of the two theories:

Incomparable interval-scale theories

Two or more theories that have interval-scale measurability, but do not have unit-scale comparability.

Example: A form of utilitarianism and a form of prioritarianism, in which the unit-scale is inconsistent.

Condensed from Moral Uncertainty (page 136):

“Consider a situation where two people, Annie and Betty, could be given a drug that extends their life by 9 years.

Situation 1: Annie and Betty have both lived for 16 years. Assume that the prioritarian’s concave function is the square root function.

Prioritarianism: 25 years - 16 years= 1 Utilitarianism: 25 years - 16 years = 9

Situation 2: Annie and Betty have both lived for 64 years. Under the same assumption:

Prioritarianism: 73 years - 64 years =~0.5 Utilitarianism: 73 years - 64 years = 9

Applying the ‘normalize the difference between saving one life and saving two’ rule does not work, and the units of scale between the two theories are inconsistent.”

Ordinal and interval-scale theories

Some theories simply do not contain interval-scale information.

Example: Plausibly, Kant’s ethical theory is an example of a merely ordinally measurable theory.

From Moral Uncertainty (page 60):

“According to Kant, murder is less choiceworthy than lying, which is less choiceworthy than failing to aid someone in need. But we don’t think it makes sense to say, even roughly, that on Kant’s view the difference in choice-worthiness between murder and lying is greater than or less than the difference in choice-worthiness between lying and failing to aid someone in need.

So someone who has non-zero credence in Kant’s ethical theory simply can’t use expected choice-worthiness maximization over all theories in which she has credence.”

Taking an Expectation Across Theories with Different Structures

Amplified theories

Uncertainty spanning across amplified theories, in which there is both interval-scale measurability and unit-scale comparability, can be compared in the same way as one would with regular empirical uncertainty.

Incomparable interval-scale theories

The example of Annie and Betty showed that even two theories with interval-scale measurability may not be unit-comparable.

In Moral Uncertainty, the authors argue for normalizing the theories in some way before attempting to make any comparison. There are plausibly a few ways of doing this:

- Range: Treat the range of the choiceworthiness function within as the same across all interval-scale and incomparable theories;

- Max-mean: Treat the difference between the mean choiceworthiness and maximum choiceworthiness as the same across all interval-scale and incomparable theories;

- Min-mean: Treat the difference between the mean choiceworthiness and minimum choiceworthiness as the same across all interval-scale and incomparable theories;

- Variance voting: Treat the variance (i.e. the average of the squared differences in choiceworthiness from the mean choiceworthiness) as the same across all theories.

Additionally, the distribution of choiceworthiness for a set of options within a theory could take many forms, including the following:

- Bipolar: i.e. a view in which violating rights is impermissible, but everything else is permissible.

- Outlier: i.e. a view in which most options have about the same level of choiceworthiness, but a small minority are extremely choiceworthy/un-choiceworthy.

- Top-heavy: i.e. a view in which most options are choiceworthy/extremely choiceworthy, but a small minority are extremely un-choiceworthy.

- Bottom-heavy: i.e. a view in which most options are un-choiceworthy/extremely un-choiceworthy, but a small minority are extremely choiceworthy.

When comparing across theories with different distributions, it would be desirable that the normalization method used does not influence which theory has a greater “say” in the MEC calculation simply due to the distribution of choiceworthiness.

While I will not dig into each example, normalizing by range gives greater “say” to a bipolar choiceworthiness distribution, normalizing by max-mean gives greater “say” to a top-heavy distribution and punishes a bottom-heavy distribution, and min-mean gives greater “say” to a bottom-heavy distribution and punishes a top-heavy distribution.

Normalizing at variance does not appear to give any greater “say” to a theory for any of the four given choiceworthiness distributions.

The authors of Moral Uncertainty provide further justification for normalizing at variance, summarized below:

- Distance from uniform theory: A theory that assigns the same degree of choiceworthiness to all options would have no “say” in an expectation calculation, so the extent to which a theory deviates from this determines the amount of “say”.

- Expected choiceworthiness of voting:

- In voting theory, voting power refers to the a priori likelihood of a person’s vote being decisive in an election.

- We should consider that, since different theories may have different degrees of credence, theories with higher credence should have higher voting power.

- Each theory could assign vastly different degrees of choiceworthiness to different options (i.e. for utilitarianism, the difference in choiceworthiness between getting pricked with a pin vs. letting a million people die).

- The difference between these options should be utilized in any expectation calculation.

- The magnitude of choiceworthiness values can be somewhat arbitrary, but choiceworthiness between options is relative. This means that each theory is described by infinitely many choiceworthiness functions, and we cannot come up with a unique value for “expected choiceworthiness”.

- The normalization used to choose an option should be the same as that used to measure “equal say”.

- In voting theory, voting power refers to the a priori likelihood of a person’s vote being decisive in an election.

Thus, the authors of Moral Uncertainty conclude that theories with interval-scale measurability that are not unit-comparable should be normalized by variance before taking an expectation.

Ordinal-scale and interval-scale theories

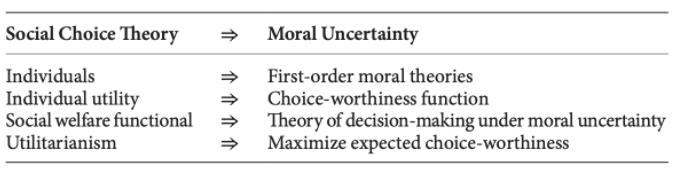

The method proposed in Moral Uncertainty to compare ordinal theories with those that contain interval-scale information draws inspiration from social choice theory.

Social choice theory studies how to aggregate individuals’ utility functions into a single ‘social’ utility function, which represents ‘social’ preferences over social states.

A social welfare functional is a function from sets of utility functions to a ‘social’ utility function.

Examples include:

- Utilitarianism, according to which A has higher social utility than B iff the sum total of utility over all individuals is greater for A than for B.

- Maximin, according to which A has higher social utility than B iff A has more utility than B for the worst-off member of society.

In the analogy with MEC, rather than individuals we have theories, and over a social welfare functional we have a theory of decision-making under moral uncertainty.

There are some key differences:

- Theories, unlike individuals, don’t all count for the same.

- To this, we can use the analogy of weighted voting in social choice theory.

- As we have discovered, a decision-maker under moral uncertainty will face varying information from different theories at the same time. Some will be:

- Interval-scale measurable and inter-theoretically comparable.

- Interval-scale measurable but inter-theoretically incomparable.

- Merely ordinally measurable.

Given the analogy with voting theory, Moral Uncertainty starts by taking a look at Condorcet extensions, which provide the gold standard voting systems.

“The idea behind such voting systems is that we should think how candidates would perform in a round-robin head-to-head tournament—every candidate is compared against every other candidate in terms of how many voters prefer one candidate to the other.

A voting system is a Condorcet extension if it satisfies the following condition: that, if, for every other option B, the majority of voters prefer A to B, then A is elected.”

This can be applied to the moral uncertainty framework:

“Let’s say that A beats B (or B is defeated by A) iff it is true that, in a pairwise comparison between A and B, the decision-maker thinks it more likely that A is more choiceworthy than B than that B is more choiceworthy than A.

A is the Condorcet winner iff A beats every other option within the option-set.”

One important condition of any voting system applied to moral uncertainty is to ensure that increasing one’s credence in some theory does not make the appropriateness ordering worse by the lights of that theory. In Moral Uncertainty, this is referred to as the condition of Updating Consistency.

It turns out that all Condorcet extensions violate this principle in some way, making it a poor candidate in the context of moral uncertainty.

However, a voting system known as the Borda Rule does not, since it regards the success of an option as equal to the sum of the magnitudes of its pairwise victories against all other options.

“To see the difference, imagine a round-robin tennis tournament, with players A–Z. Player A beats all other players, but in every case wins during a tiebreaker in the final set. Player B loses by only two points to A, but beats all other players in straight sets.

Condorcet extensions care first and foremost about whether a player beats everyone else, and would regard Player A as the winner of the tournament. The Borda Rule cares about how many points a player wins in total, and would regard Player B as the winner of the tournament.”

Applied to moral uncertainty, we get the Borda Score:

Borda Score: An option A’s Borda Score, for any theory Ti, is equal to the number of options within the option-set that are less choiceworthy than A according to theory Ti’s choiceworthiness function, minus the number of options within the option-set that are more choiceworthy than A according to Ti’s choiceworthiness function.

Which results in the Borda Rule in the context of MEC:

Borda Rule: An option A is more appropriate than an option B iff A has a higher Credence-Weighted Borda Score than B; A is equally as appropriate as B iff A and B have an equal Credence-Weighted Borda Score.

Tool Implementation

To summarise, we now have the following ways to take an expectation over moral theories with different structures.

- Amplified theories: Regular expected value calculation.

- Incomparable interval-scale theories: Variance voting.

- Ordinal-scale and interval-scale theories: Borda rule.

So how do we combine these approaches in practice?

Multi-step procedure

Intuitively, you may expect the best approach to take an expectation over different types of theory to be something along the lines of doing what you can with the most informationally rich theories, and then falling back to general techniques where less information is available.

However, Moral Uncertainty (pages 105-110) describes how this violates the aforementioned Updating Consistency requirement.

One-step procedure

In the same pages, the following “One-step” procedure is proposed:

“What we suggest is that we should normalize the Borda Scores of the ordinal theories with choice-worthiness functions by treating the variance of the interval-scale theories’ choice-worthiness functions and the variance of the ordinal theories’ Borda Scores as the same.

If we take this approach, we need to be careful when we are normalizing Borda Scores with other theories. We can’t normalize all individual comparable theories with non-comparable theories at their variance. If we were to do so, we would soon find our equalization of choice-worthiness-differences to be inconsistent with each other.

Rather, for every set of interval-scale theories that are comparable with each other, we should treat the variance of the choice-worthiness values of all options on that set’s common scale as the same as the variance of every individual non-comparable theory.”

My interpretation of this implemented in code is as follows:

- Calculate the Borda Scores for each option in each ordinal theory by the following method:

- Option Borda Score = Number of other options in theory with lower choiceworthiness ranking.

- Group all interval-scale theories by name, such that amplified versions of each theory are kept together.

- Normalize by variance all options across all amplified theories, such that variance across all options within each set of amplified theories is equal to 1.

- Normalize the borda scores of each individual ordinal theory, such that variance is equal to 1.

- Take an expectation across all options in all theories:

- Multiply each CW value for each option within each theory, by the credence in that theory.

- Sum the credence-adjusted CW values for each option.

- Output sum for each option.

Decisions in the model creation process

Here, I outline decisions made in the model creation process that I suspect have a chance of being incorrect. Of course, this may not include all errors.

Borda Score calculaton

As I see it, there are two potential issues with my implementation here:

- The Borda Score only considers the numbers of options beaten by an individual option within the same individual ordinal theory, not across theories.

- I’m about 60% sure this follows the definition of the Borda Score in the context of the one-step approach.

- The book however, shows examples of calculating a Borda Score across theories (footnotes on pages 73-74).

- Incorporating credence at this stage in the Borda Score calculation, and again when taking an expectation after normalizing unit-comparable theories by unit variance, would mean adjusting for credence twice, which seems wrong.

- It considers the numbers of options beaten by an individual option within the same ordinal theory, without subtracting the number of options that beat that option (see Borda Score definition above).

- This definition was originally intended to account for cases in which two options have equal choiceworthiness.

- In my implementation I do not allow for an ordinal theory to have two options of equal choiceworthiness, instead forcing a hierarchy.

- Adding the extra condition may take me a while to figure out and ultimately not be required, so I have left as is.

Unit variance and zero mean

When normalizing at variance, I am assuming the exact magnitude of the variance is arbitrary.

For the purpose of the model, I used the sklearn.preprocessing scale method to normalize the choiceworthiness distribution of each comparable theory set and each individual ordinal theory to have a variance = 1 and mean = 0.

Using the Moral Uncertainty Tool

Apologies that the interface is difficult to use, making it user-friendly in a separate platform would likely require a lot of effort.

First, copy a version of the Moral Uncertainty Tool to your Google Drive.

You can run cells in Google Colab using the Play button on the left of each cell, or pressing “Shift + Enter”.

Cells should be run in order, except the “Moral Uncertainty Model” form cell which should be run every time you add a new theory and its relevant information to the form.

I recommend using a spreadsheet (like this, feel free to copy to your own Google Drive) to keep track of theories, credences and choiceworthiness of options.

*Version number will be added automatically when you add theories of the same name to the model.

After running all cells, the expected choiceworthiness of each action should be output at the bottom of the workbook.

Other listening/reading

Moral uncertainty is discussed in the following 80,000 Hours episodes:

- Christian Tarsney on future bias and a possible solution to moral fanaticism

- Will MacAskill on moral uncertainty, utilitarianism & how to avoid being a moral monster

- Hilary Greaves on Pascal’s mugging, strong longtermism, and whether existing can be good for us

Michael Aird has previously written about making decisions when both morally and empirically uncertain.

Fin Moorhouse has written an in-depth summary of the arguments within Moral Uncertainty.